Terror in the Details: Western-made Components in Russia's Shahed-136 Attacks

LEGAL DISCLAIMER: This report identifies several companies and governments who are believed to be involved in the manufacturing of components which have been acquired by the Russian military and used in their military hardware.

For the avoidance of doubt, we do not allege any legal wrongdoing on the part of the companies who manufacture the components and do not suggest that they have any involvement in any sanctions evasion-related activity.

Furthermore, we do not impute that the companies which make the components are involved in directly or indirectly supplying the Russian military or Russian military customers in breach of any international (or their own domestic) laws or regulations restricting or prohibiting such action.

Where a link is drawn between manufacturers and the weapons being used in suspected war crimes, this is done solely to highlight ethical and moral concerns.

INTRODUCTION

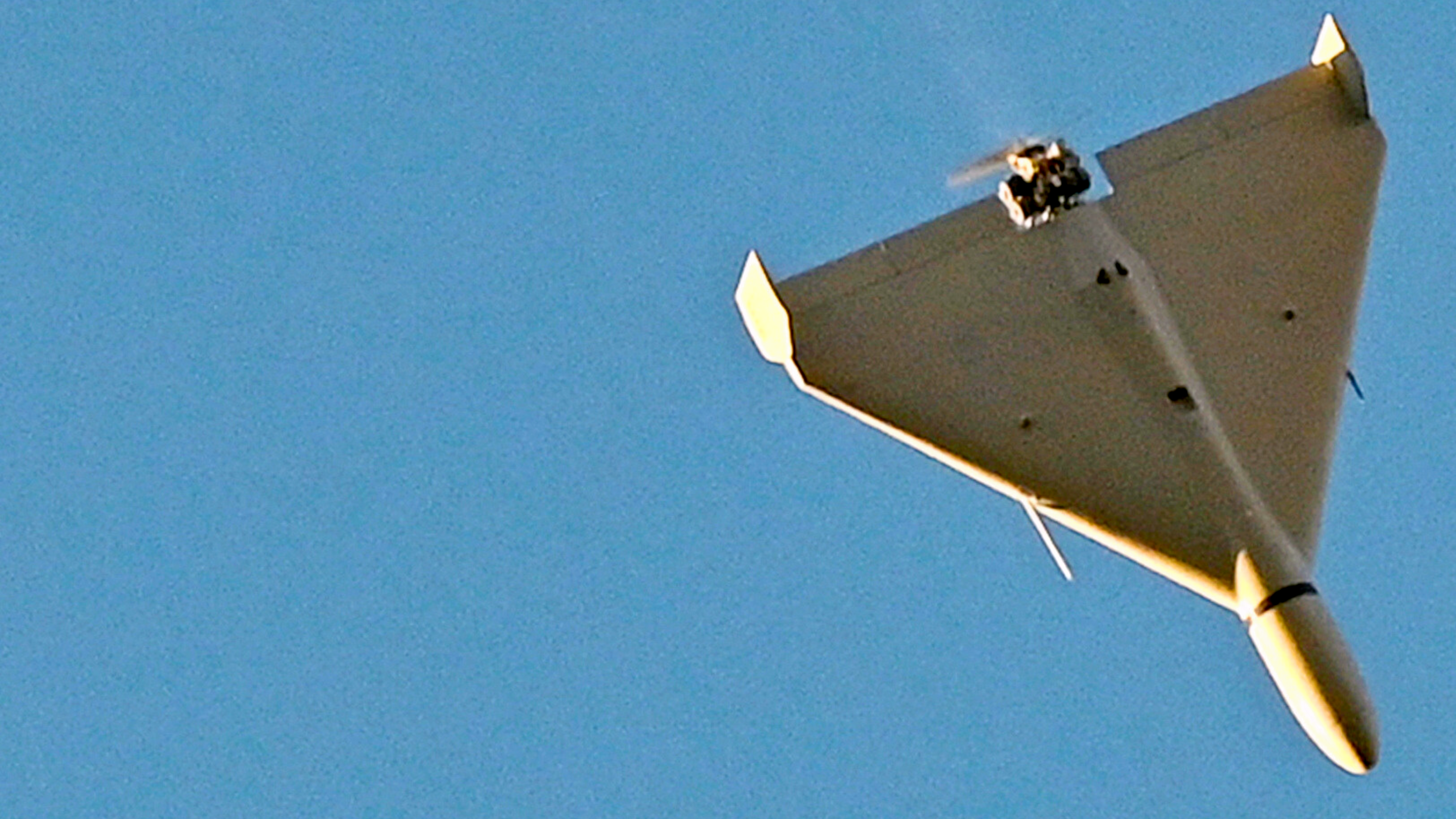

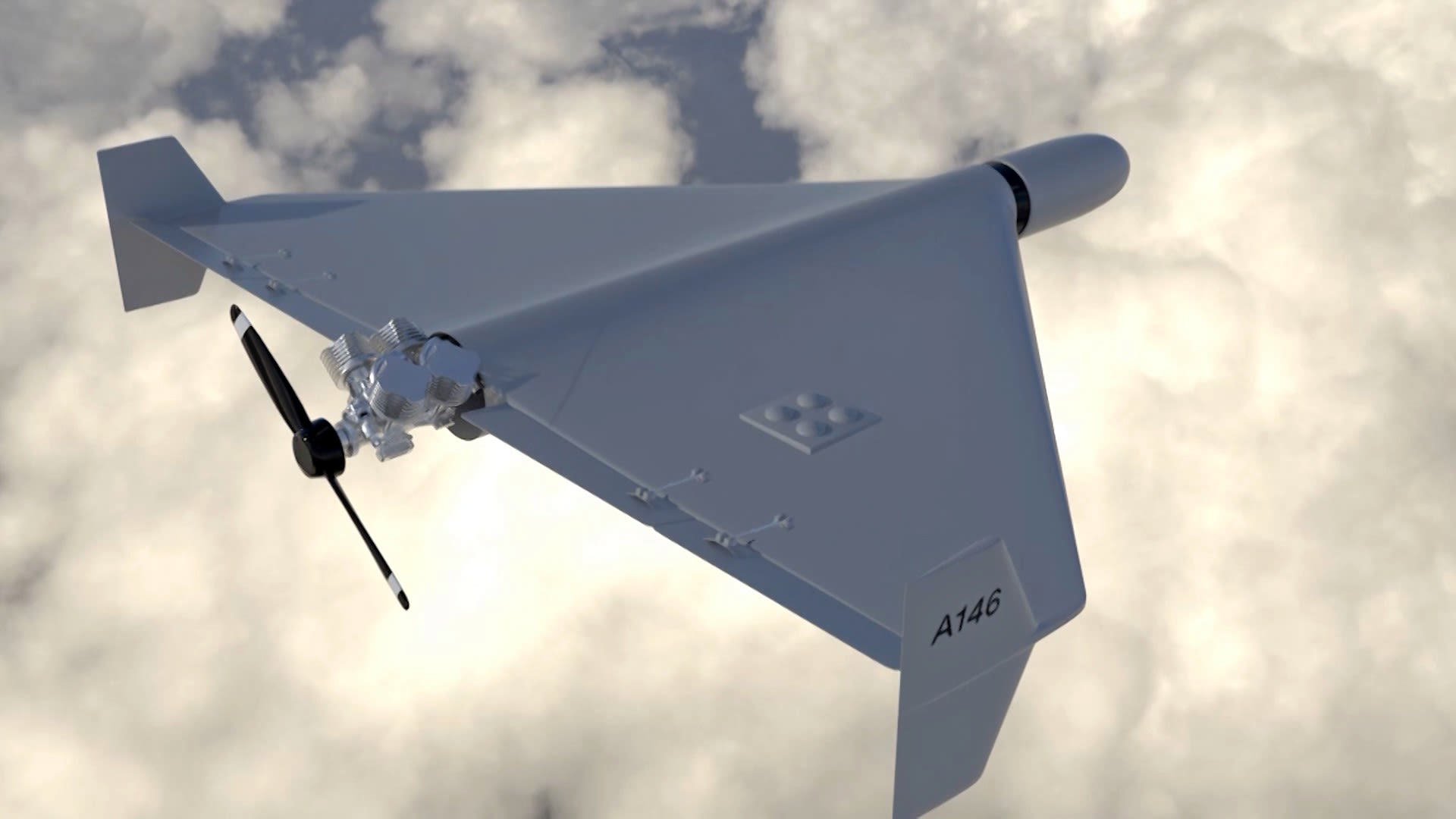

The Shahed-136 is an Iranian loitering munition that targets stationary ground objects guided by a sophisticated navigation system. Described as “ingenious in its simplicity” by Dr Uzi Rubin, the former Director of the Israel Missile Defense Organization, it flies low and slow towards a target and detonates on impact. It is both ruthlessly accurate and inexpensive.

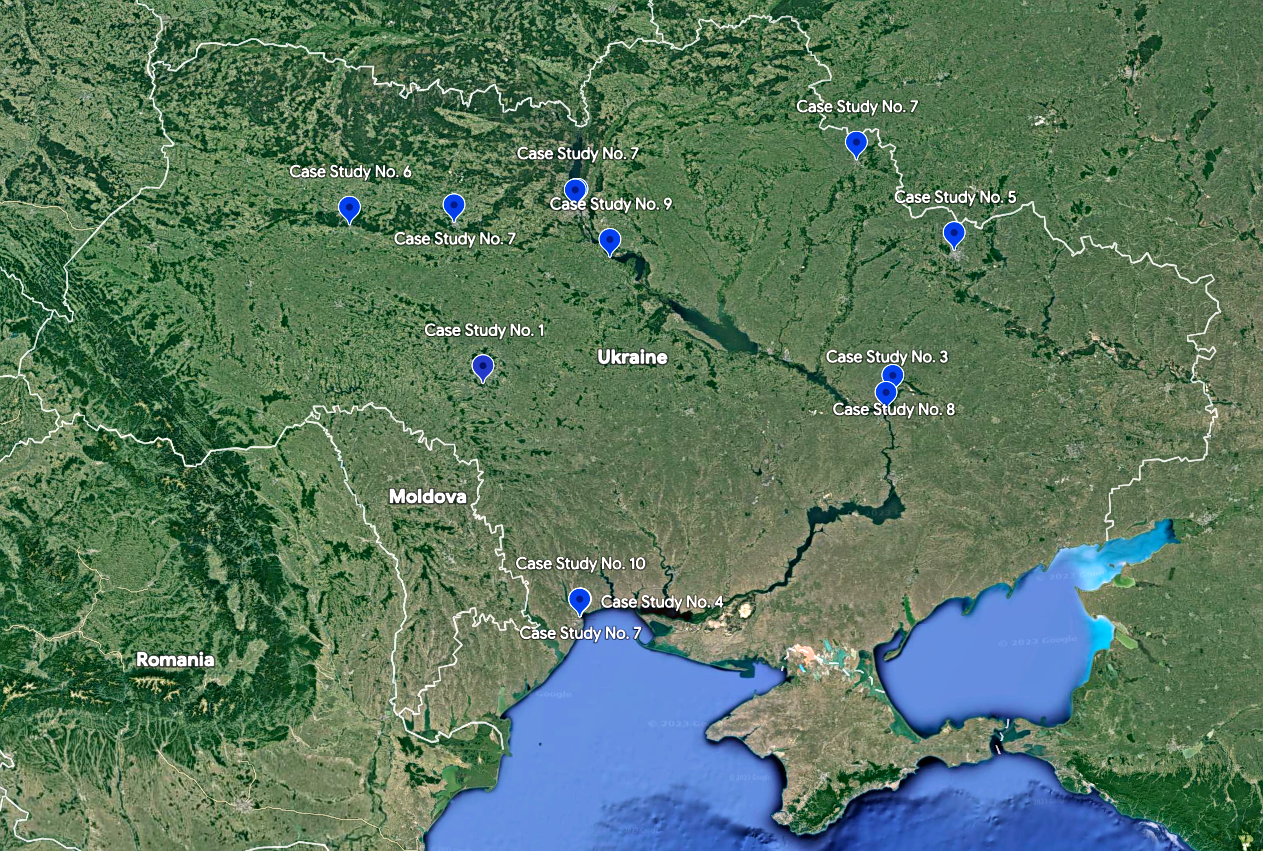

This report analyses ten suspected Russian war crimes carried out using the Shahed-136. The attacks targeted residential buildings, power plants, businesses, a school and a children's summer camp. In each instance, we have explored the circumstances around the attack, the presence of military objects or activity in the vicinity of targeted objects, the result of the attacks, including the level of damage and casualties, and the means by which we have identified the Shahed-136 as being used.

We find that Russia’s attacks are, on the face of it, intentionally aimed at the civilian population and infrastructure, with no tangible military advantage gained as a result of them. These are fundamental conditions that must be met in order for an attack to be assessed as a war crime, and in each case study, we examine the legal background behind our assessment.

This report also explores the Shahed-136’s documented reliance upon Western-made components, and in so doing, calls into question the effectiveness of sovereign export controls and corporate due diligence processes. Since Russia’s February 2022 invasion, Western governments have worked to supply the Ukrainian armed forces with equipment, support, and training, but have done little to exploit the Russian military’s Achilles heel: its reliance upon Western components.

"The Shahed 136's simplicity, combined with its almost uncanny accuracy, long range and low cost, makes it unique among strategic standoff weapons"

In total, components from 16 companies based in the US, Japan, Canada, and Switzerland have been found inside the Shahed-136, ranging from microprocessors and semiconductors to ethernet transceivers and memory.

These findings are consistent with a wide range of existing research, including our previous report – ‘Enabling War Crimes? Western-Made Components in Russia’s War Against Ukraine’ – that has explored the extent to which the weapons at the heart of Russia’s committing of atrocities are, ‘under the hood’, reliant upon Western-made components in order to function.

Restricting Russia’s access to such components would have a devastating and immediate effect on sustaining its war effort. Operating at a high tempo requires an equally high level of resupply and replenishment: Russia’s drones, missiles, communication systems, and other equipment require regular repairs, maintenance, and restocking – all processes that require, to varying degrees, Western components. It would be just weeks before Russia’s supply of these components dried up, which would have significant consequences on the battlefield.

This report serves two purposes. Firstly, to illustrate Russia’s continued unlawful and barbaric assaults on the Ukrainian population, judged to be in conflict with International Humanitarian Law. Secondly, to sound the alarm as to the Russian military's reliance on Western-made components in its war against Ukraine and the urgent need to restrict the continued supply of such components.

The beginning of the solution is to recognise that the problem exists. Up to now, businesses and policymakers alike have remained predominantly silent on the issue of Russia’s reliance on Western-made components. This has been justified, at least in part, by the fact that the causes of the situation – including the Russian military’s supply chain – are difficult to track and as such, a challenge to put right. The reality, however, as this report demonstrates, is that civil society organisations and research groups can, using open-source intelligence, expose and trace these causes with immense precision.

Lack of evidence or lack of understanding can no longer be used as a justification for inaction.

PART ONE: WHAT IS A WAR CRIME?

What is an IHL violation?

International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is a set of rules and principles that seeks to protect persons who are not or no longer directly or actively participating in hostilities and imposes limits on the means and methods of warfare.

An IHL violation is a violation of this set of rules, which can be found in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, the Hague Conventions of 1907 and customary international law, which are the core sources of modern IHL.

IHL is part of public international law, which is made up primarily of international treaties (formed by states parties), customary international law (formed by “a general state practice accepted as law”) and general principles of law (legal norms existing among the majority of nations). IHL applies once the conditions for an armed conflict are factually met on the ground. For international armed conflicts, these conditions consist of one or more states’ use of armed force against one or more other states, and for non-international armed conflicts. Armed confrontation between governmental armed forces and one or more non-state armed groups, or between such groups, may amount to non-international armed conflict and thus be governed by IHL if it reaches a certain level of intensity and organisation of non-state parties involved.

What is a war crime?

The core principle behind the concept of war crimes is that individuals can be held criminally accountable for serious violations of IHL.

A serious IHL violation that amounts to a war crime must include one (or several) of the following three types of conduct:

- Endangering protected persons, e.g. willful killings, torture, intentional attacks on civilians, killing of combatants rendered hors de combat (incapable of fighting);

- Endangering protected objects, e.g. intentionally attacking civilian objects including civilian dwellings, hospitals, schools; and

- Breaching important values even without physically endangering persons or objects directly, e.g. declaring that no quarter will be given, subjecting persons to humiliating treatment, violating the right to a fair trial.

Currently, the most comprehensive list of examples of serious violations of IHL (war crimes) is contained in Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

War crimes, together with crimes against humanity, genocide, and the crime of aggression, are four core international crimes. These crimes are considered to be of such gravity that they have no statute of limitation under international criminal law, meaning that those committing the crimes can be brought to justice no matter how much time has passed since their commission.

The implementation of IHL is primarily the responsibility of states. They must respect, and ensure respect for, these rules in all circumstances. IHL is universal: all parties fighting in a conflict are obliged to respect it, be they governmental forces or non-state armed groups. The responsibility to prevent and punish IHL violations also belongs primarily to states. IHL requires states to investigate serious violations and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects. This means that appropriate steps must be taken to implement the legal framework for criminal prosecution of IHL violations into a state’s domestic criminal law. As a complement to domestic trials, internationally established criminal justice mechanisms, including the International Criminal Court (ICC), may promote greater respect for IHL by ensuring that the most serious IHL violations, e.g. war crimes, do not go unpunished.

Who can prosecute IHL violations and war crimes?

States must adopt legislation and regulations aimed at ensuring full compliance with IHL. Additionally, states must investigate war crimes committed by their nationals or armed forces or on their territory and, if possible, prosecute the suspects. Some states have also adopted national legislation allowing the prosecution of war crimes in their national courts, irrespective of the nationality of the offender or the place where the violations were committed (universal jurisdiction). Domestic prosecution is, however, often impossible during or in the aftermath of an armed conflict if the regime that perpetrated the crimes retains power and is unwilling to prosecute its own representatives.

Over the past 30 years, the international community has stepped in on several occasions to bridge the impunity gap created by the failure of domestic accountability by creating international ad hoc tribunals (ICTY/R), hybrid tribunals (ECCC, SCSL, STL) and the ICC. The latter is a permanent international judicial body with jurisdiction over any core crime committed on the territory of its 123 member states or by its nationals, and, in some cases, when a situation is referred to the Prosecutor of the ICC by the UN Security Council or a country submits a declaration with the Registrar of the ICC accepting the exercise of the ICC’s jurisdiction, non-member states. Ukraine did not ratify the Rome Statute but recognised the jurisdiction of the ICC over international crimes committed on the territory of Ukraine from 21 November 2013 by submitting two declarations of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine to the ICC in 2014 and 2015. After Ukraine recognised the ICC's jurisdiction, the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC (OTP) conducted a seven-year-long preliminary examination and, in 2022, opened an investigation into the situation in Ukraine. On 17 March 2023, the OTP issued arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova for their alleged responsibility for the war crime of unlawful deportation of children and the unlawful transfer of children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.

These and other suspected perpetrators can be tried by ICC and, if found guilty, sentenced to up to 30 years in prison or to a term of life imprisonment when justified by the extreme gravity of the crime and the individual circumstances of the convicted person.

PART TWO: SUSPECTED WAR CRIMES CARRIED OUT BY THE SHAHED-136 IN UKRAINE

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is the first international armed conflict involving the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as weapons at this scale. Between September 2022, when Russia first began using widespread UAV attacks, and May 2023, it launched more than 1,000 UAVs to attack Ukrainian critical energy and civilian infrastructure.

By the end of 2022, Russian attacks on energy infrastructure had left millions of Ukrainians without heating, electricity, water and other vital services during the cold winter months. As of 31 January 2023, at least 116 civilians have been killed, and at least 379 more have been injured in such attacks.

In May 2023, Russia intensified its aerial attacks against Ukrainian cities, launching at least 20 waves of UAVs and missiles. On the night of 28 May 2023, Kyiv alone was attacked by 54 Shahed 136/131, making it the largest Russian UAV attack to date.

As demonstrated throughout this report, there is no evidence to suggest that Russian aerial attacks have affected the Ukrainian military or decision-making centres significantly. Instead, these attacks are part of the broader pattern of the Russian military’s intentional terror campaign against the Ukrainian people.

The authors of this report documented 25 Russian UAV attacks on Ukraine between September 2022 and May 2023. Cases were discarded where there was insufficient information to establish the target’s status (military/civilian), the level of damage caused, or the model of the UAV used in the attack. Ten attacks were then selected for inclusion in this report, on the basis that they caused serious damage and civilian casualties, and used the Shahed-136.

The attacks documented in this report killed 15 civilians and injured another 42. In addition, they destroyed or damaged nine critical infrastructure objects, 13 civilian houses and four other civilian objects.

The Shahed-136 is considered to be a guided weapon. It navigates using a combination of GPS and GLONASS, while a commercial-grade digital communication chip within it allows for a target’s location to be updated mid-flight, or even for the intended target to be changed entirely while still in the air.

Targets are selected and struck with precision, and it is therefore reasonable to assume that in the case studies below and the plethora of other strikes in recent months, the Shahed-136 is impacting its intended target, rather than experiencing any level of deviation.

The ten attacks analysed in this report may constitute grave breaches of IHL and war crimes of directing attacks against protected civilian objects and directing attacks against civilians. Additional investigations would be required to corroborate these allegations to a judicial standard.

Case Study No. 1

Date: 11 October 2022

Location: Ladyzhyn, Vinnytsia Oblast

Incident: Attack on energy infrastructure

On 11 October 2022, Russian forces attacked energy infrastructure across six regions in western, central and southern Ukraine. According to the Ukrainian military, the attacks were carried out using Kh-101 missiles and Shahed-136 UAVs.

One of the Shahed-136 attacks damaged a thermal power plant in Ladyzhyn, Vinnytsia Oblast. A second strike, following shortly after the first one, injured six emergency workers who were responding to the first attack. The attacks caused severe damage to the Ladyzhyn power plant, leaving some 18,000 civilians without heating for at least two months during winter.

Case Study No. 2

Date: 17 October 2022

Location: Kyiv

Incident: Attack on energy infrastructure, an apartment building, and an office building

On the morning of 17 October 2022, Russian forces attacked Ukrainian cities with missiles and UAVs, directing some 28 UAVs at Kyiv. The first attack took place at around 7 a.m. and targeted an office building in Shevchenkivskyi District, setting it on fire and damaging several nearby residential buildings.

The use of the Shahed-136 was confirmed by both the US Defence Intelligence Agency and the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The Mayor of Kyiv, Vitaliy Klitschko, published a photo of one of the UAV’s remnants; this can be identified as the Shahed-136.

The second attack followed an hour later. Four UAVs targeted several energy infrastructure facilities and an apartment building in downtown Kyiv. The attack on the apartment building killed five civilians, including a pregnant woman. 19 more civilians were rescued from under the rubble. Three people, including two rescue workers, were hospitalised with injuries. As a result of the attack, the 120-year-old apartment building – which was part of Kyiv's historical downtown – was damaged beyond repair.

UAV and missile attacks on Kyiv, Sumy and Dnipropetrovsk regions that day caused black-outs in hundreds of settlements across the regions.

Case Study No. 3

Date: 9 November 2022

Location: Dnipro, Ukraine

Incident: Attack on a building of a delivery company

On the night of 9 November 2022, Russian forces launched a UAV attack on a storage facility used by the Nova Poshta delivery company in Dnipro.

The fire caused by the attack significantly damaged the building and destroyed most of its equipment and parcels. Four Nova Poshta employees were hospitalised with severe injuries.

Local authorities published pictures of Shahed-136 remnants discovered at the scene. The Russian Ministry of Defense described this attack as “the destruction of the ammunition of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.” The Office of the Prosecutor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast said however that there were no military targets in the area that was attacked. No military personnel were killed or wounded. Additionally, the company’s Terms and Conditions prohibit the shipment of any weapons and there is no evidence of any direct cooperation or relationship between the Armed Forces of Ukraine and Nova Poshta.

Case Study No. 4

Date: 10 December 2022

Location: Odesa Oblast

Incident: Attack on energy infrastructure

On 10 December 2022, Russian forces launched a UAV attack on two energy infrastructure facilities in Odesa Oblast. It took firefighters more than four hours to extinguish the fire started by the attack. The attack caused a total electricity blackout in Odesa and Odesa Oblast, which affected some 1.5 million residents. The next day, 300,000 people were still without electricity. Local authorities had to mandate restrictions on energy use in the region for the following five days as a result of the damage reducing the network’s ability to fulfil demand.

The Odesa Regional Prosecutor’s Office confirmed that Russian forces used the Shahed-136 to carry out the attack.

Case Study No. 5

Date: 28–29 December 2022

Location: Kharkiv

Incident: Attack on energy infrastructure

On the night of 28–29 December 2022, Russian forces attacked critical energy infrastructure in Kharkiv with 13 UAVs. 11 of them were shot down by Ukrainian Air Defence while two hit critical infrastructure, leaving some 1,000 civilian homes without heating.

The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the Kharkiv Regional Prosecutor’s Office reported that the UAVs used in the attacks were Shahed-136.

Case Study No. 6

Date: 10 February 2023

Location: Shepetivka, Khmelnytskyi Oblast

Incident: Attack on energy infrastructure

On 10 February 2023, Russian forces launched a massive attack on Ukraine with 20 Shahed-136/131 UAVs and 71 Kh-101, X-555 and Kalibr missiles. Local authorities reported Shahed-136/131 attacks in Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.

One UAV damaged a critical infrastructure facility in Shepetivka, Khmelnytska Oblast, causing a fire and a two-day blackout.

The local authorities reported that the Ukrainian Air Defence shot down four Russian Shahed-136/131 that were trying to target energy infrastructure facilities in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.

Case Study No. 7

Date: 8–9 March 2023

Location: Kyiv, Zhytomyr, Sumy, and Odesa regions

Incident: Large-scale attacks on civilian objects and energy infrastructure

On the night of 8–9 March 2023, Russian forces attacked Ukrainian civilian infrastructure across Ukraine with eight Shahed-136/131 UAVs and 81 missiles, including Kh-101 and Kalibr.

In Zhytomyr Oblast, a UAV hit an energy infrastructure facility, leaving 150,000 civilian users without electricity and water until the evening.

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast meanwhile was attacked by UAVs, missiles and artillery fire, causing significant damage to the energy infrastructure and killing one civilian. Other UAVs were shot down over Kyiv and Sumy Oblast.

Case Study No. 8

Date: 18 March 2023

Location: Novomoskovsk, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Incident: Attack on energy infrastructure and civilian houses

On the night of 18 March 2023, Russian forces launched an attack with five UAVs on Novomoskovsk, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. Two UAVs hit and significantly damaged a critical infrastructure object with oil products, destroyed four nearby civilian houses and damaged another six.

The General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces confirmed that the attack was launched by a Shahed-136 UAV.

Case Study No. 9

Date: 22 March 2023

Location: Rzhyshchiv, Kyiv Oblast

Incident: Attack on two dormitories and a school

On the night of 22 March 2023, Russian forces attacked Kyiv Oblast and Zhytomyr Oblast with 21 Shahed-136/131 UAVs. In Rzhyshchiv, Kyiv Oblast, the UAVs hit a school and two adjacent dormitories. Nine people were killed, and 29 more were injured, according to local officials. The attack partially destroyed one of the school buildings and the two dormitories, causing a massive fire. As a result of the attack and the fire, more than 200 people had to be evacuated from the area.

Case Study No. 10

Date: 19–20 April 2023

Location: Odesa

Incident: Attack on a children’s summer camp

On the night of 20 April 2023, Russian forces attacked Odesa with 12 UAVs. Two drones targeted a children’s summer camp, causing a fire in one of its buildings.

Odesa District Military Administration and Ukrainian air defence confirmed the use of the Shahed-136 UAVs, the remnants of which were found at the impact site.

Potential legal classification

The ten cases of Russian attacks on Ukrainian civilian and energy infrastructure analysed above are part of the broader pattern of Russian forces’ intentional terror campaign against the Ukrainian population.

An attack on civilian infrastructure can only be justified if it is proved to represent a concrete military advantage. Even where a military objective is identified, the attack’s lawfulness is a question of proportionality – measured by pitting the concrete military advantage being sought against the harm that the attack causes to the civilian population. Where harm is disproportionate to the advantage being sought, the attack violates IHL and may amount to a war crime.

The Russian High Command has claimed that its attacks on civilian infrastructure are aimed against the “military command system of Ukraine and related energy facilities”.

The Ukrainian government, Ukrainian army representatives, and national and international military experts have said however that the Ukrainian Armed Forces are energy-autonomous and the Russian attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure do not affect either Ukrainian military capacity or its progress/advances on the battlefield. Thus, Russian attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure provide the Russian armed forces with very little, if any, military advantage.

As of February 2023, Russian forces have attacked some 250 energy facilities, mostly cogeneration plants and electricity substations, leaving more than ten million households without power. As of 31 January 2023, at least 116 civilians have been killed, and at least 379 more have been injured in these attacks. Without electricity, water and fuel, hundreds of healthcare facilities were unable to operate to their full capacity and the power outages posed severe risks to the lives of their patients, especially those dependent on electric life-support machines. As a result of Russian attacks on critical infrastructure, millions of people were at times deprived of access to clean water, heating and the ability to cook hot meals.

In addition to energy infrastructure, Russian armed forces have targeted residential buildings, a school, a children’s summer camp and a delivery business, which on the face of it, are not of any military value. These attacks have claimed 14 civilian lives and injured at least another 36.

Comments by the Russian leadership and state propaganda illustrate that the attacks have aimed to terrorise the civilian population, retaliate against Ukrainian counter-attacks and put pressure on Ukrainian authorities to abandon their resistance. According to President Putin, attacks on the energy infrastructure will be “commensurate with the level of threat to the Russian Federation”. His press secretary later clarified that the attacks are part of Russia’s negotiation tactics, adding: “The unwillingness of the Ukrainian side to settle the problem, to start negotiations, its refusal to seek common ground – this is their consequence". Members of the Russian parliament were more candid, calling on Ukrainian civilians to “rot and freeze” and describing the attacks as “necessary to destroy the Ukrainian state’s capacity to survive”. Consequently, there is a reasonable basis to believe that these attacks are aimed not at a substantial military advantage but at the civilian population. At the very least, the Russian attacks cause disproportionate harm to the civilian population to the military advantage being sought – harm which the Russian military and civilian leadership appear to disregard and even encourage.

IHL prohibits violence or threats, “the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population.” Such tactics are also prohibited by the Russian Federation’s Military Manual.

The Shahed-136 is considered to be a guided weapon. It navigates using a combination of GPS and GLONASS, while a commercial-grade digital communication chip within it allows for a target’s location to be updated mid-flight, or even for the intended target to be changed entirely while still in the air.

Targets are selected and struck with precision, and it is therefore reasonable to assume that the case studies show the Shahed-136 impacting its intended and premeditated target, rather than experiencing any level of deviation.

In conclusion therefore, the Russian attacks on eight energy infrastructure objects across seven Ukrainian regions, ten residential buildings in Novomoskovsk, an office in Kyiv, a school in Rzhyshchiv, a children’s summer camp in Odesa and a delivery business in Dnipro, on the face of it, represent grave breaches of IHL and may amount to the war crime of directing attacks against protected civilian objects.

Additionally, Russian attacks on some of these objects, particularly, energy infrastructure in Dnipropetrovsk and Vinnytsa regions, an apartment building in Kyiv, two dormitories in Rzhyshchiv and a delivery business in Dnipro, which left 15 civilians dead and 42 more injured may amount to the war crime of directing attacks against civilians.

PART THREE: THE SHAHED-136 AND ITS RELIANCE ON WESTERN COMPONENTS

Usually given the name ‘Geranium’ inside Russia, the Shahed-136 is an Iranian-made ‘one-way attack’ (OWA) UAV, meaning each aircraft is used once to fly towards a designated target, detonating on impact. Amid Russia’s ongoing difficulties maintaining high-tempo missile strikes, the Shahed-136 has proved a key weapon in its arsenal. It is believed to have a range of up to 2,500km, using a combination of Global Navigation Satellite System and GLONASS to reach its intended target, while its warhead, at between 40 and 50 kg, is effective against soft, unprotected targets.

Dr Uzi Rubin, the former Director of the Israel Missile Defense Organization, previously described the Shahed-136’s “simplicity, combined with its almost uncanny accuracy, long range and low cost” as making it entirely unique as a strategic standoff weapon.

Dr Rubin noted that this precision and range, combined with a small yet powerful warhead, renders the Shahed-136 for all practical purposes a “propeller-driven cruise missile”.

The origin of the Shahed-136 is uncertain, but Iran has been employing drones in its military operations since the 1980s. In recent decades, a range of new UAVs have been exhibited during annual Iranian military parades and the country is known to manufacture several types of drones. It has been alleged that these drones are then supplied to various groups including Hezbollah in Lebanon and Houthi rebels in Yemen. According to the Pentagon, Iranian-allied forces have utilised these drones in attacks against US military personnel in Syria, including one such attack in August 2022 against the US-run base at Tanf.

The Shahed-136, the most advanced of these drones, was first publicly named by Israel's Prime Minister Naftali Bennett in September 2021. In July 2022, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said the White House believed Iran was preparing to provide Russia with hundreds of drones, adding that Iran would also train Russian military personnel to use them.

In October 2022, the United States National Security Council told reporters that “a relatively small number” of Iranian trainers and technicians were in Crimea “to help the Russians use [the drones] with better lethality.” Russians remotely piloted the aircraft with Iranian personnel “assisting”.

While it is not known precisely how many Shahed-136s have been supplied to Russia, Ukraine's intelligence services have claimed that Russia ordered approximately 2,400 of the type.

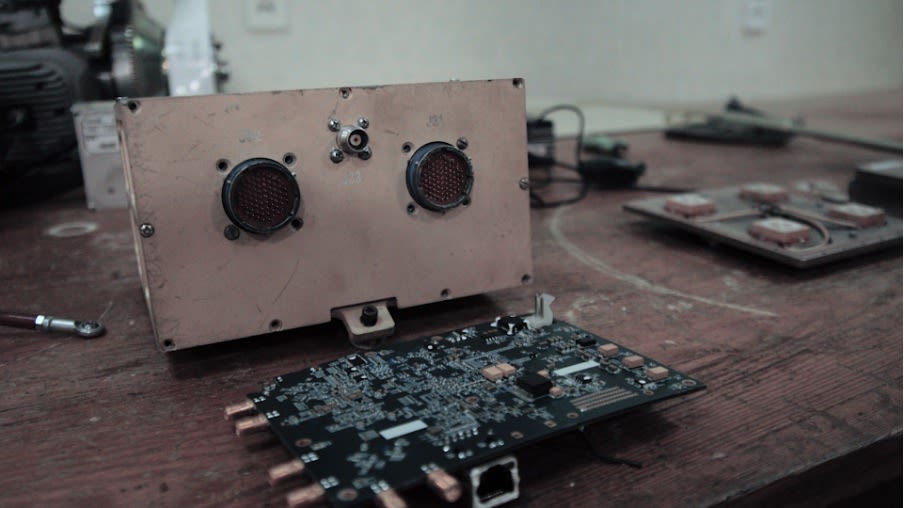

NAKO’s analysis of two different Shahed-136s, downed in Odesa and Cherkasy in 2022, revealed them as having a range of Western components originating from the US, Japan, Canada, and Switzerland. The type of components found inside the Shahed-136 vary, but it's clear they provide a genuine and substantial contribution to its overall capability.

Companies whose components have been found inside the Shahed-136 are listed below.

SPI Serial Flash Memory with Dual-I/O and Quad-I/O Support manufactured by Adesto Technologies.

A range of components manufactured by Analog Devices, including:

- RF Transceivers

- ADI 12-Output Clock Generators with 2.8GHz VC

- Linear CMOS regulators with low drop

- 16-bit analog-to-digital converters

- Output voltage/current drivers with output signal range

A spokesperson for Analog Devices said: “As a global public company, Analog Devices is committed to complying with all applicable laws and regulations in the countries where we operate.

“Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and in compliance with U.S. and EU sanctions, Analog Devices ceased business activities in Russia, and in the Russian-backed regions of Ukraine and Belarus, and promptly instructed all of our distributors to halt shipments of our products into these regions. Any post-sanctions shipment into these regions is a direct violation of our policy and the result of an unauthorized resale or diversion of ADI products.”

Microprocessors manufactured by Freescale Semiconductor, an American company now owned by NXP Semiconductors.

A spokesperson for NXP Semiconductors said: “We do not tolerate the use of our products in Russian or Iranian weapons, or any other application our products were not designed or licensed for. We continue to comply with export control and sanctions laws in the countries where we operate and we do not support any business in or with Russia, Belarus, and other fully embargoed countries, including Iran. Our team is in ongoing contact with regulators around the world on this issue, as we explore additional measures to help neutralize illegal chip diversion.”

Micro-components made by Hemisphere GNSS, a US manufacturer based in Arizona.

A High Voltage Giant Torque Servo, a form of ultra-precise and efficient electrical motor, manufactured by Hitec USA Group.

Buffer line driver manufactured by International Rectifier, now part of Infineon.

Our previous report – 'Enabling War Crimes? Western-Made Components in Russia's War Against Ukraine' – identified components bearing the name of Cypress Semiconductor, another company that has been acquired by Infineon, inside the Iskander, Kh-101, and Kalibr missiles.

Ethernet transceivers, allowing for point-to-point network and data transfer, manufactured by Marvell Technology. Components bearing the name of Marvell have previously been identified in Russia's Kalibr cruise missile.

A spokesperson for Marvell said: “Marvell is appalled that any of its products are used in Russian weapons. Marvell does not sell to the Russian military or government. We have a strong export compliance program and have no knowledge how these parts have found their way into Russia.”

Multichannel RS-232 Line Driver/Receiver manufactured by Maxim Integrated.

Low dropout linear regulators manufactured by Micrel Semiconductor, now owned by Microchip Technology.

Microchip said: “Microchip does not sell products into countries where our technology is prohibited from sale such as Iran, Russia, Belarus, or sanctioned regions in the Ukraine. We condemn the illegal use of our products. We take our responsibility as a good corporate citizen seriously, and comply with applicable laws, including export controls and trade sanctions. We take care to maintain supply chain integrity by various methods including screening customers against restricted party lists. We also partner with government authorities and law enforcement, as necessary.

"Microchip is a leading provider of smart, connected, and secure embedded control solutions with more than 120,000 customers across the industrial, automotive, consumer, aerospace and defense, communications, and computing markets. Our products have many possible customer applications. Distributors also sell our products into the marketplace.

"Diversion of legally sold products is an industry-wide issue. Microchip is participating in a U.S. Industry Working Group led by the U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security to further discuss these matters. For more information, see the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) statement titled Semiconductor Industry is Committed to Combatting Illicit Chip Diversion. Microchip is a member of SIA and our CEO is on the SIA board of directors.”

Parallel NOR flash memory and multilayer ceramic chip capacitors manufactured by Micron Technology.

The Shahed-136's airspeed sensor board containing non-isolated DC/DC converters manufactured by MinMax Technology. The presence of MinMax components in Iranian military equipment was previously reported by Atlantic Council in 2020.

High speed CMOS octal bus buffer manufactured by ON Semiconductor.

A range of microcontrollers, digital signal processors, instrumentation amplifiers, power modules and voltage regulators manufactured by Texas Instruments. Components manufactured by Texas Instruments have previously been identified within the Iskander, Kh-101, and Kalibr missiles.

A spokesperson for Texas Instruments said: “TI is not selling any products into Russia, Belarus or Iran. TI stopped sales to Russia and Belarus at the end of February 2022, and we no longer support sales there. TI complies with applicable laws and regulations in the countries where we operate. We do not support or condone the use of our products in applications for which they weren’t designed.”

EMI/RFI filters manufactured by Murata.

GLONASS, GPS Ceramic Patch RF Antenna manufactured by Tallysman.

A spokesperson for Tallysman said: “We were made aware and agree that some of our components have been misused in sophisticated military guidance systems in Ukraine. Tallysman is 100% committed to supporting Ukraine in the face of Russian aggression. Tallysman produces GNSS (also known as GPS) patch elements, that are highly desired globally for positioning, navigation, and timing systems. The Tallysman ceramic patch antennas recovered are typical of what can be found in a consumer Satnav device. They are normally used for survey equipment, precision agriculture, timing systems, fleet management, and many other applications. Tallysman has been and will continue to be fully compliant and cooperative with all Canadian and international agencies and export controls. Unfortunately, products like antennas, printed circuit boards, semiconductors, resistors, capacitors, screws, wires, etc., with significant engineering effort can be used for malevolent purposes and unintended applications. To the extent possible for a product sold globally, we examine and review end customer identities and intended end uses. We are hyper vigilant about what products we sell to whom.”

Microcontrollers and linear regulators manufactured by STMicroelectronics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

As detailed throughout this report, the Shahed-136, containing Western-made components, has been used to carry out what are suspected to be war crimes in Ukraine. The supply and maintenance of Russia’s weapons is a key vulnerability in its campaign against Ukraine, and it is the duty of policymakers and businesses to exploit this vulnerability.

In light of this report’s findings, the authors offer the following recommendations:

1. Sanctions and embargoes: Countries should consider implementing further targeted sanctions or embargoes on specific individuals, entities, or sectors involved in the transfer of Western components to Russia's military-industrial complex. These measures should be implemented in coordination with like-minded countries to maximise their impact.

Moreover, it is clear that such sanctions require greater monitoring and enforcement in order to truly be effective. This is an area where governments can cooperate effectively with civil society, NGOs, and think tanks. Western companies and NGOs have easily available open-source intelligence tools at their fingertips, whether they are commodity trading platforms or automatic identification system-based vessel tracking websites. These tools empower watchdog organisations and risk assessment committees in governmental and non-governmental organisations to monitor malign transfers of products and technologies that would undermine sanctions efficacy.

2. Strengthen export controls: Countries should enhance their export control mechanisms and regulations to restrict the transfer of sensitive military technology and components to Russia. This includes stricter scrutiny of export licences and a comprehensive review of end-user certificates. These countries should also study the supply chain to prevent the export of Western components from third countries to Russia.

3. Company due diligence: Companies must exercise greater diligence in assessing the ultimate purpose for which their products are utilised, as emphasised in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. It is strongly recommended that companies carefully consider the conclusions presented in these reports and acknowledge the possible material risks associated with future products.

For companies engaged in cross-border transactions involving items that are restricted under Russia-related export controls, it is prudent to implement a compliance policy reasonably designed to prevent, deter, and detect violations. Such a policy and related procedures should cover

- Screening of counterparties against U.S. sanctions- and export control-related restricted party lists;

- Identification of export-controlled products and implementation of related internal controls;

- Training of employees; and

- Periodic testing of the functionality of the compliance program.

Regarding third-party diversion risk in particular, companies can take the following steps:

- Conduct reasonably robust due diligence on third parties such as resellers, distributors, and sales agents;

- Obtain from counterparties “end-user certificates,” confirming the intended end-use and end-user of the products;

- Incorporate compliance-related terms into contracts with counterparties; and

- Conduct periodic audits of sales/distribution channels.

Ignorance as to a product’s end-user should not be relied upon as a moral or legal defence.

4. Diplomatic efforts: An international, and solution-focused conversation to examine ways in which the flow of western-made components can be ceased. Governments, political leaders, and businesses alike have a duty to engage with this conversation and explore solutions.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) is an independent, non-governmental organisation founded in 2008. With a presence in Brussels, Kyiv, and Tbilisi, IPHR works closely with civil society groups in Eastern Europe, South Caucasus, and Central Asia to raise human rights concerns at the international level and promote respect for the rights of vulnerable communities. IPHR has been documenting atrocity crimes committed in the context of Russia’s war on Ukraine since 2014 and has been using collected evidence for accountability purposes.

The Independent Anti-Corruption Commission (NAKO) is a voluntary, non-profit, non-partisan organisation pursuing the goals of minimising opportunities for corruption in Ukraine’s defence sector through strong research, effective advocacy, and increased public awareness. NAKO was established as a program of the Transparency International Defence and Security program in 2016 and since then has evolved as a self-standing organisation within the Transparency International global movement.

Truth Hounds is a team of experienced human rights professionals documenting war crimes and crimes against humanity in conflict contexts since 2014. Truth Hounds fights against impunity for international crimes and grave human rights violations through investigation, documentation, monitoring, advocacy and problem solving for vulnerable groups. Truth Hounds documenters mobilise all available resources and documentation methodology to create a systemic approach to its documentation work, and promote accountability for grave human rights abuses and international crimes.

Global Diligence LLP is a partnership of established international lawyers with practical experience of living and working in high-risk areas. Global Diligence team advises and represents States, businesses, organisations, or individuals on international criminal law and human rights. Focused on challenges in unstable and conflict-affected regions, Global Diligence provides mapping, training, and project management for capacity building programs.